Let’s talk about the quintessential English landscape! If you’ve been to the National Gallery in London, chances are you’ve stood in front of John Constable’s (1776-1837) The Haywain. A highlight of room 34, this painting is largely considered Constable’s greatest work, if not the most important work in English landscape painting. By the time it was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1824, fellow Romantic painters, Theodore Gericault (1791-1824) and Eugene Delacroix (1798-1863) were in admiration of the new direction Constable was taking landscape.

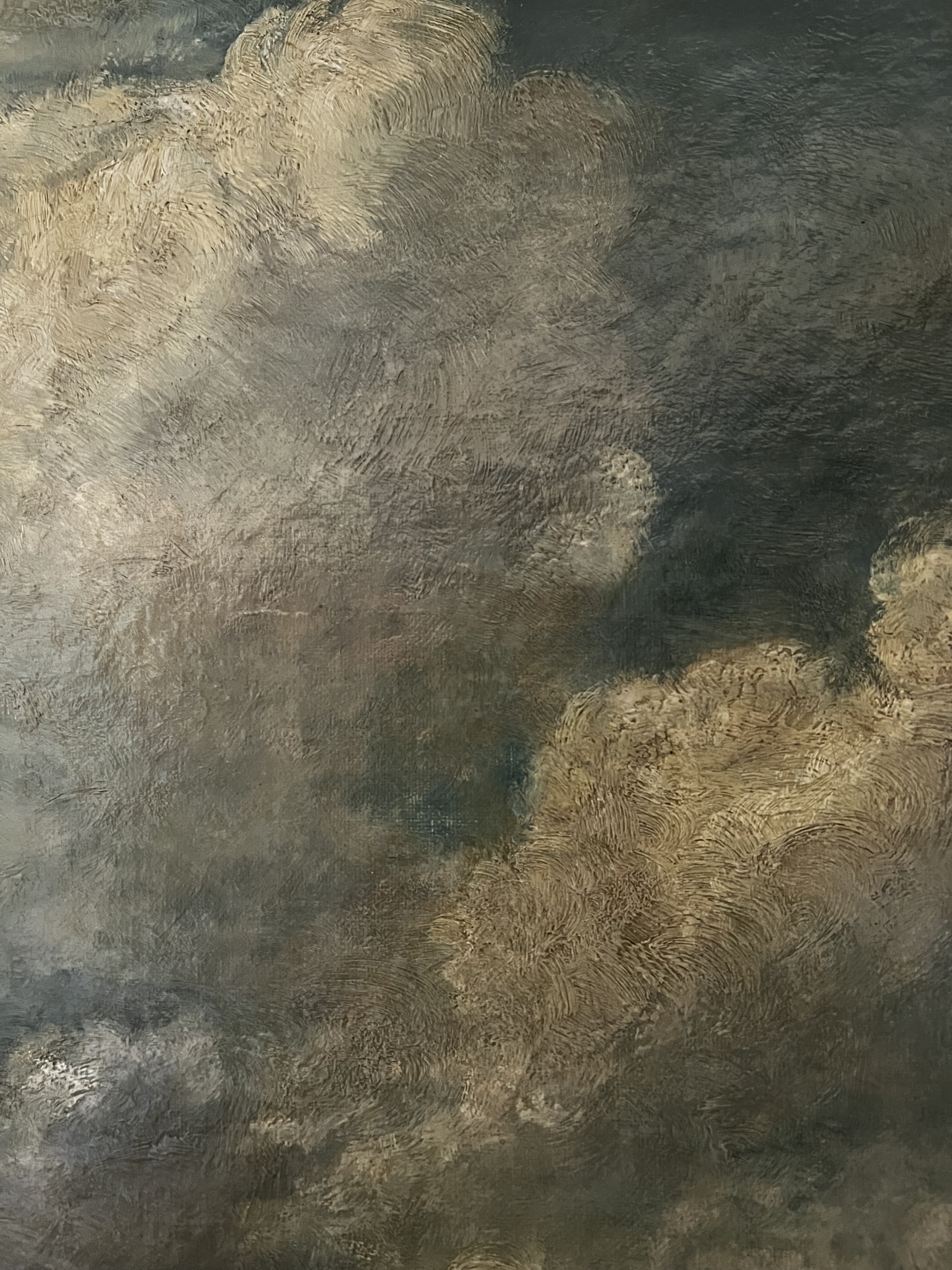

However, my aim here is not to recap the importance and origins of Constable’s Haywain, that’s been done a million times over. Today, we are going to talk about this work: An 1893 copy of the Haywain.

It is not just a copy, but a capstone achievement, a marker, if you will, of great talent, and moreover it provides us with art history insights worth chatting about.

But first, let me provide a quick background on the original!

Although it seems traditional now, at the time that Constable painted the work, in 1821, it was very radical. Constable was born in Suffolk, England and his wealthy merchant parents allowed him to study at the Royal Academy at the young age of 24! The Royal Academy was still teaching the rudiments of old master painting. First and foremost, the most important genres of painting were history, biblical, or mythological paintings followed by portraiture. Landscape paintings were typically not painted on as large a scale. Constable’s Haywain is over 4 x 6 ft in height and width. Second, Constable’s bright greens and unique brushstrokes and dabs were quite innovative for the time.

Constable spent 10 years sketching the countryside, including his family’s mill, featured in the bottom right of the painting. Constable is also well known for his cloud studies. All of this sketching prepared him to paint the work quickly in his London studio. True to the romantic movement, Constable’s close attention to nature created a beautiful atmosphere which renders the scene immortal. 19th century art critic Francis Gerard wrote:

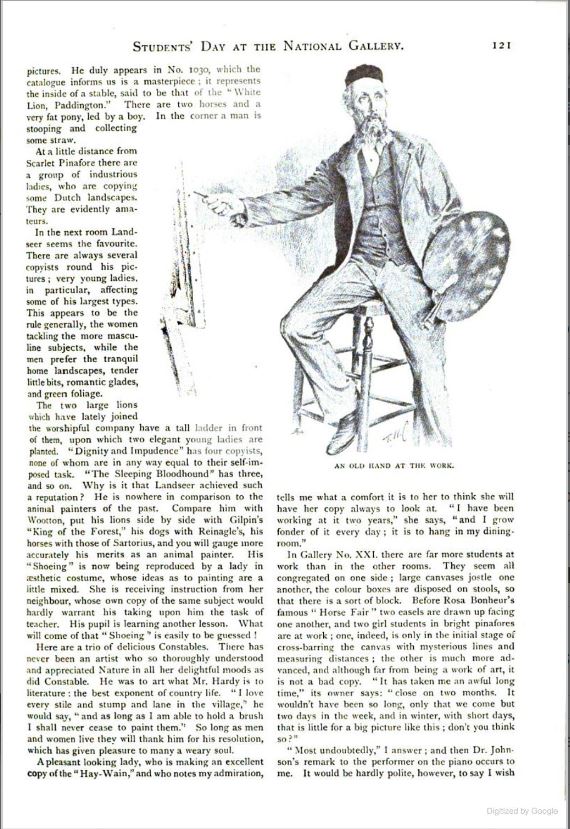

“There has never been an artist who so thoroughly understood and appreciated Nature in all her delightful moods as did Constable. He was to art what Mr. Hardy is to literature: the best exponent of country life. ‘I love every stile and stump and lane in the village,’ he would say, ‘and as long as I am able to hold a brush, I shall never cease to paint them.’ So long as men and women live, they will thank him for his resolution, which has given pleasure to many a weary soul.”[1]

But Constable, who had been dead for decades, didn’t paint our painting. Clearly an artist copied the formative work. This painting evidences a trend that was quite common in the 19th century, copyists!

About Copyists:

“Copyists” were students or amateur artists who spent days in the National Gallery copying the works of the masters. Starting in 1880, the National Gallery opened their copyist program to the general public. Students could pay a small fee and gain access to the museum on specific days in order to sit in the gallery and copy. It was a very popular scheme. In fact, Cassell’s Family Magazine reported in 1893 that on student days, Thursdays and Fridays, the Gallery is full of student artists, stating “they are artists who come to make their own copies either on commission or for sale on their own account. “[2]

Registering as a copyist said little about the artist’s level of talent and even less about their relative fame. For instance, one of my favorite artists, John Singer Sargent (1856-1925) registered as a copyist at the Prado in 1895.[3] Sargent is arguably one of the foremost artists of the 19th century and yet he registered to study and copy the works of the masters.

Copyists could apply for admission for around 3 months at a time, in which they could sit and paint in front of the paintings of their choice. According to the National Gallery’s website, in 1884, copyists visited the galleries 26,435 separate times and over 1,000 copies in oil were made. There was even a medal awarded to the best copy of an old master, though this was abolished at the end of the 19th century. Could our painting have won that award?

Unfortunately, the trend became unpopular at the turn of the 20th century. In the October 1903 edition of the Museum’s Journal, a debate ensued regarding copyists in the galleries. Citizens were launching complaints, but the journal noted that the National Galleries were founded, “not only for the pleasure of the citizen but as places of education where in students, copying, improve their own abilities or might spread the love of pictures, and so indirectly do service to the greater public and to the art of England.”[4] Despite this notion, most of the copyists, by this time, were amateurs who never intended to make a living as an artist. Thus, the trend of copyists would only decline as the century progressed on.

We have little doubt that our painting was done by a copyist. Based on the signature and date, it seems most likely that a copyist registered with the National Gallery in 1893 and chose to paint an oil copy of Constable’s the Haywain. My efforts to track down the copyist have been, as of yet, unsuccessful. Partly, this is due to the loss of records. The gallery’s copyist records from 1855- 1901 have not survived. Therefore, it makes it difficult to track exactly who was in the gallery in 1893.

However, we do have a firsthand report from the Gallery from 1893, the year our painting was completed that might shed a little light. Art critic Francis Gerard visited the Gallery during one of the student days in 1893. In the Gallery with Constable’s Haywain, the reporter saw three “delicious” Constables copies being completed. Could one of these three paintings be ours? Writing further, Gerard notes an encounter with one woman painting a Constable copy.

A pleasant looking lady, who is making an excellent copy of the “Hay-Wain,” and who notes my admiration, tells me what a comfort it is to her to think she will have her copy always to look at. “I have been working at it two years,” she says, “and I grow fonder of it every day; it is to hand in my dining-room.” [5]

Could this Haywain copy be the one that hangs in our kitchen today? Certainly, TCL could be this amateur woman artist. In any case, it is a fantastic copy that shows off the skill and attention to detail that the artist possessed.

While I am not resigned to end my search for the artist. For now, what can be said of the painter is that he or she was clearly very talented. This detailed imitation of the Haywain captures the atmosphere of the English countryside, the clouds, the trees and the mill, with the same Romantic ideals that Constable implemented.

Subscribe for more!

[1] Gerard, Francis. A., “Students’ Day at the National Galley,” Cassell’s Family Magazine. United Kingdom: Cassell, 1893, 121.

[2] Ibid., 119.

[3] Fairbrother, Trevor J.. John Singer Sargent: The Sensualist. United Kingdom: Seattle Art Museum, 2000.

[4] “Copyists in Art Galleries,” The Museums Journal. October 1903. (United Kingdom: Museums Association, 1904), 143. https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_Museums_Journal/Bb09AQAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=National+Gallery+Copyists&pg=RA1-PA143&printsec=frontcover

[5] Gerard, Francis. A., “Students’ Day at the National Galley,” Cassell’s Family Magazine. United Kingdom: Cassell, 1893, 121.

One response to “John Constable’s The Haywain and Copyists in the Gallery”

I am not really sure of what type of comment you would like? I really loved the story that was printed here about JOHN CONSTABLE that I have just read. Very intriguing & have learned alot from it

I read alot about it, because I have a painting of “THE HAY WAIN”that is sitting in my bedrm. I have tried FOREVER to get inquiries & estaments about it, but find it very difficult to do. If you could please provide me with any information I would greatly appreciate it. Thank You! Sandy VanNess at sandrasvn8@gmail.com

LikeLike